At some time later today I will be crossing the 2,000,000 hits mark and

I have you my viewers, the casual observers and the occasional wandering wayfarer to thank for it.

So I would like to send out a big hardy Thank You, a Whoop and a Hip Hip Huzzah!!! To all of you!

Here's to the next million hits!

Translate

Sunday, July 17, 2016

Saturday, July 9, 2016

Leonardo Da Vinci's Great Kite

Here are some images of Edu-Toys Leonardo Da Vinci's Great Kite.

From the instructions"

Da Vinci was a prolific inventor; he designed hundreds of war machines for work, but also for theatre and the world of music. Of all the machines he invented, the flying machines were the most incredible, and not a single book on the world of aviation fails to recognize Leonardo Da Vinci as the forerunner in studies of human flight.

The Codex of Flight, preserved in the Royal Library of Turin represents the most advanced and organic state of Da Vinci's studies on flight. The genius of Da Vinci drew inspiration for his work from his direct observation of the flight of a bird; the Kite. By analyzing the Turin notebook carefully, the Leonardo3 Research centre discovered that the design for the "Codex of Flight flying machine" is described with extreme precision.

Da Vinci described its dimensions, the materials with which it is to be built, its shape and how it works; the whole notebook revolves precisely around the construction and use of the machine. The piloting must have been complex. He would use his hands and feet that could activate ropes and rotate, move and open and close the wings with his own movements. Da Vinci's design is not drawn in its entirety. We must therefore reconstruct the indispensable parts. These include; the canvas to cover the wings, some articulations and pulleys, and the tail, which Da Vinci knew was indispensable for controlling the machine. Da Vinci's instructions for building the machine are extremely precise and even regard the materials to be used. He also advised which ones to avoid.

On folio 7r of the Codex of flight he wrote: ... not one single piece of metal must be used in the construction, because this material breaks or wears away under stress, so there is no need to complicate the job.

Da Vinci suggested using resistant leather for the joints and silk for the ropes. The canvas would be taffeta, a very thick silk, or linen canvas that is starched so any holes are sealed to prevent any air from passing through. Also with regards to the canvas that would cover the wings he suggested referring to the wing membrane of a bat since, unlike bird feathers, air does not pass through it...

"Remember that your bird must only copy the bat because the membranes act as a framework, Connecting the major articulations. If you wanted to copy the wings of feathered birds you would would have to remember that they have stronger bones and quills because they are permeable; the feathers are divided and the air passes through them. On the other hand, the bat is held up by its membranes, which connect everything together and are not permeable.

We can presume the rest of the machine was to be made of wood, using different species based on their properties: ash wood for the wings, because it's flexible; beech wood for the pulleys, since it's easy to polish; and walnut wood or something else more resistant for the structural parts. The Great Kite, described and drawn in the Codex of Flight, is one of the most complex flying machines that Da Vinci designed. It's likely that Da Vinci never finished building it, but he profoundly believed that his project was worthwhile and fervently desired to test it, launching it, with a pilot (some poor sap), on the edge of a mountain top. In fact, in one of the most famous phrases from the Codex of Flight, Da Vinci wrote:

"The first Great Bird will make its first flight, launched from the peak of Mount Cecero and will fill the universe with amazement and all the reports of its great fame will confer eternal glory upon the places where it was conceived".

From the instructions"

Da Vinci was a prolific inventor; he designed hundreds of war machines for work, but also for theatre and the world of music. Of all the machines he invented, the flying machines were the most incredible, and not a single book on the world of aviation fails to recognize Leonardo Da Vinci as the forerunner in studies of human flight.

The Codex of Flight, preserved in the Royal Library of Turin represents the most advanced and organic state of Da Vinci's studies on flight. The genius of Da Vinci drew inspiration for his work from his direct observation of the flight of a bird; the Kite. By analyzing the Turin notebook carefully, the Leonardo3 Research centre discovered that the design for the "Codex of Flight flying machine" is described with extreme precision.

Da Vinci described its dimensions, the materials with which it is to be built, its shape and how it works; the whole notebook revolves precisely around the construction and use of the machine. The piloting must have been complex. He would use his hands and feet that could activate ropes and rotate, move and open and close the wings with his own movements. Da Vinci's design is not drawn in its entirety. We must therefore reconstruct the indispensable parts. These include; the canvas to cover the wings, some articulations and pulleys, and the tail, which Da Vinci knew was indispensable for controlling the machine. Da Vinci's instructions for building the machine are extremely precise and even regard the materials to be used. He also advised which ones to avoid.

On folio 7r of the Codex of flight he wrote: ... not one single piece of metal must be used in the construction, because this material breaks or wears away under stress, so there is no need to complicate the job.

Da Vinci suggested using resistant leather for the joints and silk for the ropes. The canvas would be taffeta, a very thick silk, or linen canvas that is starched so any holes are sealed to prevent any air from passing through. Also with regards to the canvas that would cover the wings he suggested referring to the wing membrane of a bat since, unlike bird feathers, air does not pass through it...

"Remember that your bird must only copy the bat because the membranes act as a framework, Connecting the major articulations. If you wanted to copy the wings of feathered birds you would would have to remember that they have stronger bones and quills because they are permeable; the feathers are divided and the air passes through them. On the other hand, the bat is held up by its membranes, which connect everything together and are not permeable.

We can presume the rest of the machine was to be made of wood, using different species based on their properties: ash wood for the wings, because it's flexible; beech wood for the pulleys, since it's easy to polish; and walnut wood or something else more resistant for the structural parts. The Great Kite, described and drawn in the Codex of Flight, is one of the most complex flying machines that Da Vinci designed. It's likely that Da Vinci never finished building it, but he profoundly believed that his project was worthwhile and fervently desired to test it, launching it, with a pilot (some poor sap), on the edge of a mountain top. In fact, in one of the most famous phrases from the Codex of Flight, Da Vinci wrote:

"The first Great Bird will make its first flight, launched from the peak of Mount Cecero and will fill the universe with amazement and all the reports of its great fame will confer eternal glory upon the places where it was conceived".

Friday, July 8, 2016

Leonardo Da Vinci's Arch Bridge

Here are some images of Academy Hobby Model Kits Leonardo Da Vinci's Arch Bridge.

From the instructions"

The design uses a self supporting arch concept to distribute weight through the full curve of the arch.

The more weight the bridge carries, the stronger it becomes.

On the other hand, if one key component is removed, the bridge will fall.

It was originally intended as a quick build, wood bridge for use by the military.

Removing a single piece of wood while the enemy was crossing could cause the bridge to collapse drowning enemy forces.

From the instructions"

The design uses a self supporting arch concept to distribute weight through the full curve of the arch.

The more weight the bridge carries, the stronger it becomes.

On the other hand, if one key component is removed, the bridge will fall.

It was originally intended as a quick build, wood bridge for use by the military.

Removing a single piece of wood while the enemy was crossing could cause the bridge to collapse drowning enemy forces.

Tuesday, July 5, 2016

Motor Torpedo Boat PT-109

Here are some images of Italeri's 1/35 scale Motor Torpedo Boat PT 109.

From Wikipedia"

PT-109 was a PT boat (Patrol Torpedo boat) last commanded by Lieutenant, junior grade (LTJG) John F. Kennedy (later President of the United States) in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Kennedy's actions to save his surviving crew after the sinking of PT-109 made him a war hero, which proved helpful in his political career.

The incident may have also contributed to Kennedy's long-term back problems. After he became president, the incident became a cultural phenomenon, inspiring a song, books, movies, various television series, collectible objects, scale model replicas, and toys. Interest was revived in May 2002, with the discovery of the wreck by Robert Ballard. PT-109 earned two battle stars during World War II operations.

PT-109 belonged to the PT-103 class, hundreds of which were completed between 1942 and 1945 by Elco in Bayonne, New Jersey. PT-109's keel was laid 4 March 1942 as the seventh Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) of the 80-foot-long (24 m)-class built by Elco and was launched on 20 June. She was delivered to the Navy on 10 July 1942, and fitted out in the New York Naval Shipyard in Brooklyn.

The Elco boats were the largest PT boats operated by the U.S. Navy during World War II. At 80 feet (24 m) and 40 tons, they had strong wooden hulls of two layers of 1-inch (2.5 cm) mahogany planking. Powered by three 12-cylinder 1,500 horsepower (1,100 kW) Packard gasoline engines (one per propeller shaft), their designed top speed was 41 knots (76 km/h; 47 mph).

For space and weight-distribution reasons, the center engine was

mounted with the output end facing forward, with power transmitted

through a Vee-drive gearbox to the propeller shaft. Because the center

propeller was deeper, it left less of a wake, and was preferred by

skippers for low-wake loitering. Both wing engines were mounted with the

output flange facing aft, and power was transmitted directly to the

propeller shafts.

The engines were fitted with mufflers on the transom to direct the exhaust under water, which had to be bypassed for anything other than idle speed. These mufflers were used not only to mask their own noise from the enemy, but to improve the crew's chance of hearing enemy aircraft, which were rarely detected overhead before firing their cannons or machine guns or dropping their bombs.

PT-109 could accommodate a crew of three officers and 14 enlisted, with the typical crew size between 12 and 14. Fully loaded, PT-109 displaced 56 tons. The principal offensive weapon was her torpedoes. She was fitted with four 21-inch (53 cm) torpedo tubes containing Mark 8 torpedoes. They weighed 3,150 pounds (1,430 kg) each, with 386-pound (175 kg) warheads and gave the tiny boats a punch at least theoretically effective even against armored ships.

Their typical speed of 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph) was effective against shipping, but because of rapid marine growth buildup on their hulls in the South Pacific and austere maintenance facilities in forward areas, PT boats ended up being slower than the top speed of the Japanese destroyers and cruisers they were assigned to attack in the Solomons. Torpedoes were also useless against shallow-draft barges, which were their most common targets. With their machine guns and 20 mm cannon, the PT boats could not return the large-caliber gunfire carried by destroyers, which had a much longer effective range, though they were effective against aircraft and ground targets.

Because they were fueled with aviation gasoline, a direct hit to a PT boat's engine compartment sometimes resulted in a total loss of boat and crew. In order to have a chance of hitting their target, PT boats had to close to within 2 miles (3.2 km) for a shot, well within the gun range of destroyers. At this distance, a target could easily maneuver to avoid being hit. The boats approached in darkness, fired their torpedoes, which sometimes gave away their positions, and then fled behind smoke screens.

Sometimes retreat was hampered by seaplanes dropping flares to render the boats visible in darkness. They would then attack the boats with bombs and machine gun fire. The firing of the boats' torpedoes imposed an additional risk of detection. The Elco launch tubes used 3-inch (76 mm) black powder charges to expel the torpedoes. Firing of the charge could sometimes ignite the grease with which the torpedoes were coated to facilitate their release from the tubes. The resultant flash could give away the position of the boat. Crews of PT boats relied on their smaller size, speed and maneuverability, and darkness, to survive.

Ahead of the torpedoes on PT-109 were two depth charges, omitted on most PTs, one on each side, about the same diameter as the torpedoes. These were designed to be used against submarines, but were sometimes used by PT commanders to confuse and discourage pursuing destroyers. PT-109 lost one of her two Mark 6 depth charges a month before Kennedy showed up when the starboard torpedo was inadvertently launched during a storm without first deploying the tube into firing position. The launching torpedo sheared away the depth charge mount and some of the footrail.

PT-109 had a single 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft mount at the rear with "109" painted on the mounting base, two open rotating turrets (designed by the same firm that produced the Tucker automobile), each with twin M2 .50 cal (12.7 mm) anti-aircraft machine guns at opposite corners of the open cockpit, and a smoke generator on her transom. These guns were effective against attacking aircraft.

The day before her final mission, PT-109's crew lashed a U.S. Army 37 mm antitank gun to the foredeck, replacing a small, 2-man life raft. Timbers used to secure the weapon to the deck later helped save their lives when used as a float.

PT-109 was transported from the Norfolk Navy Yard to the South Pacific in August 1942 on board the liberty ship SS Joseph Stanton. PT-109 arrived in the Solomon Islands in late 1942 and was assigned to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 2 based on Tulagi island. PT-109 participated in combat operations around Guadalcanal from 7 December 1942 to 2 February 1943 when the Japanese withdrew from the island.

Despite having a bad back, JFK used his father Joseph P. Kennedy's influence to get into the war. He started out in October 1941 as an ensign with a desk job for the Office of Naval Intelligence. Kennedy was reassigned to South Carolina in January 1942 because of his brief affair with Danish journalist Inga Arvad. On 27 July 1942, Kennedy entered the Naval Reserve Officers Training School in Chicago.

After completing this training on 27 September, Kennedy voluntarily entered the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadrons Training Center in Melville, Rhode Island, where he was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) (LTJG). He completed his training there on 2 December. He was then ordered to the training squadron, Motor Torpedo Squadron 4, to take over the command of motor torpedo boat PT-101, a 78-foot Huckins PT boat.

In January 1943, PT-101 and four other boats were ordered to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 14 (RON 14), which was assigned to Panama. He detached from RON 14 in February 1943 while the squadron was in Jacksonville, Florida, preparing for transfer to the Panama Canal Zone.

The Allies had been in a campaign of island hopping since securing Guadalcanal in a bloody battle in early 1943. Seeking combat duty, Kennedy transferred on 23 February 1943, as a replacement officer to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 2, which was based at Tulagi Island in the Solomon Islands. Traveling to the Pacific on USS Rochambeau, Kennedy arrived at Tulagi on 14 April and took command of PT-109 on 23 April. On 30 May, several PT boats, including PT-109, were ordered to the Russell Islands in preparation for the invasion of New Georgia.

After the capture of Rendova Island, the PT boat operations were moved to a "bush" berth there on 16 June. From that base, PT boats conducted nightly operations, both to disturb the heavy Japanese barge traffic that was resupplying the Japanese garrisons in New Georgia, and to patrol the Ferguson and Blackett Straits in order to sight and to give warning when the Japanese Tokyo Express warships came into the straits to assault U.S. forces in the New Georgia–Rendova area.

On 1 August, an attack by 18 Japanese bombers struck the base, wrecking PT-117 and sinking PT-164. Two torpedoes were blown off PT-164 and ran erratically around the bay until they ran ashore on the beach without exploding. Despite the loss of two boats and two crewmen, Kennedy's PT-109 and 14 other boats were sent north on a mission through Ferguson Passage to Blackett Strait, after intelligence reports had indicated that five enemy destroyers were scheduled to run that night from Bougainville Island through Blackett Strait to Vila, on the southern tip of Kolombangara Island.

In the PT attack that followed, fifteen boats loaded with 60 torpedoes counted only a few observed explosions. However, of the thirty torpedoes fired by PT boats from the four divisions not a single hit was scored. Many of the torpedoes exploded prematurely or ran at the wrong depth. The boats were ordered to return when their torpedoes were expended, but the boats with radar shot their torpedoes first. When they left, remaining boats, including PT-109, were left without radar, and were not notified that other boats had already engaged the enemy.

PT-109, PT-162, and PT-169 were ordered to continue patrolling the area in case the enemy ships returned. Around 2:00 a.m. on 2 August 1943, on a moonless night, Kennedy's boat was idling on one engine to avoid detection of her wake by Japanese aircraft when the crew realized they were in the path of the Japanese destroyer Amagiri, which was returning to Rabaul from Vila, Kolombangara, after offloading supplies and 900 soldiers. Amagiri

was traveling at a relatively high speed of between 23 and 40 knots (43

and 74 km/h; 26 and 46 mph) in order to reach harbor by dawn, when

Allied air patrols were likely to appear.

The crew had less than ten seconds to get the engines up to speed, and were run down by the destroyer between Kolombangara and Ghizo Island, near 8°3′S 156°56′E.

Conflicting statements have been made as to whether the destroyer captain had spotted and steered towards the boat. Some reports suggest Amagiri's captain never realized what happened until after the fact. The author Donovan, having interviewed the men on the destroyer, concluded that it was not an accident. Damage to a propeller slowed the Japanese destroyer's trip to her own home base.

The captain of Amagiri was Lieutenant Commander Kohei Hanami. Also aboard was his senior officer, Captain Katsumori Yamashiro (commander, 11th Destroyer Flotilla), and on a following ship was Captain Tameichi Hara (Flotilla commander, Destroyer Div. #7), who claimed he noticed the resulting explosive fire after PT-109 had been rammed, cut in half, and left burning.

PT-109 was cut in two. Seamen Andrew Jackson Kirksey and Harold W. Marney were killed, and two other members of the crew were badly injured. For such a catastrophic collision, explosion, and fire, it was a low loss rate compared to other boats that were hit by shell fire. PT-109 was gravely damaged, with watertight compartments keeping only the forward hull afloat in a sea of flames.

PT-169 launched two torpedoes that missed the destroyer and PT-162's

torpedoes failed to fire at all. Both boats then turned away from the

scene of the action and returned to base without checking for survivors.

The eleven survivors clung to PT-109's bow section as it drifted slowly south. By about 2:00 p.m., it was apparent that the hull was taking on water and would soon sink, so the men decided to abandon it and swim for land. As there were Japanese camps on all the nearby large islands, they chose the tiny deserted Plum Pudding Island, southwest of Kolombangara. They placed their lantern, shoes, and non-swimmers on one of the timbers used as a gun mount and began kicking together to propel it. Kennedy, who had been on the Harvard University swim team, used a life jacket strap clenched between his teeth to tow his badly-burned senior enlisted machinist mate, MM1 Patrick McMahon. It took four hours to reach their destination, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) away, which they reached without interference by sharks or crocodiles.

The island was only 100 yards (91 m) in diameter, with no food or water. The crew had to hide from passing Japanese barges. Kennedy swam to Naru and Olasana islands, a round trip of about 2.5 miles (4.0 km), in search of help and food. He then led his men to Olasana Island, which had coconut trees and drinkable water.

The explosion on 2 August was spotted by an Australian coastwatcher, Sub-lieutenant Arthur Reginald Evans, who manned a secret observation post at the top of the Mount Veve volcano on Kolombangara, where more than 10,000 Japanese troops were garrisoned below on the southeast portion. The Navy and its squadron of PT boats held a memorial service for the crew of PT-109 after reports were made of the large explosion.

However, Evans dispatched islanders Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana in a dugout canoe to look for possible survivors after decoding news that the explosion he had witnessed was probably from the lost PT-109. They could avoid detection by Japanese ships and aircraft and, if spotted, would probably be taken for native fishermen.

Kennedy and his men survived for six days on coconuts before they were found by the scouts. Gasa and Kumana disobeyed an order by stopping by Naru to investigate a Japanese wreck, from which they salvaged fuel and food. They first fled by canoe from Kennedy, who to them was simply a shouting stranger. On the next island, they pointed their Tommy guns at the rest of the crew since the only light-skinned people they expected to find were Japanese and they were not familiar with either the language or the people.

Gasa later said "All white people looked the same to me." Kennedy convinced them they were on the same side. The small canoe was not big enough for passengers. Though the Donovan book and movie depict Kennedy offering a coconut inscribed with a message, according to a National Geographic interview, it was Gasa who suggested it and Kumana who climbed a coconut tree to pick one. Kennedy cut the following message on a coconut:

The message was delivered at great risk through 35 nmi (65 km; 40 mi) of hostile waters patrolled by the Japanese to the nearest Allied base at Rendova. Other coastwatcher natives who were caught had been tortured and killed. Later, a canoe returned for Kennedy, taking him to the coastwatcher to coordinate the rescue. PT-157, commanded by Lieutenant William Liebenow, was able to pick up the survivors.

The arranged signal was four shots, but since Kennedy only had three bullets in his pistol, Evans gave him a Japanese rifle for the fourth signal shot. The sailors sang "Yes Jesus Loves Me" to pass the time. Gasa and Kumana received little notice or credit in military reports, books, or movies until 2002 when they were interviewed by National Geographic shortly before Gasa's death.

In a more recent visit to the area, writer/photographer Jad Davenport managed to track down the then-90-year-old Eroni Kumana, and together they made a visit to view Kennedy Island. In typical fashion for the time, Kumana reports that the first thing the survivors asked for was cigarettes. When they realized they had no matches, Kumana surprised and delighted the men by making a fire by rubbing two sticks together.

The coconut shell came into the possession of Ernest W. Gibson, Jr. who was serving in the South Pacific with the 43rd Infantry Division. Gibson later returned it to Kennedy. Kennedy preserved it in a glass paperweight on his Oval Office desk during his presidency. It is now on display at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts.

Kennedy's coconut message was not the only message given to the coastwatchers. A more detailed message was written by the executive officer of PT-109, Leonard Jay Thom. Thom's message was a "penciled note" written on paper. Kennedy's message was written on a more hidden location in case the native coastwatchers were stopped and searched by the Japanese.

Thom's message read:

From Wikipedia"

PT-109 was a PT boat (Patrol Torpedo boat) last commanded by Lieutenant, junior grade (LTJG) John F. Kennedy (later President of the United States) in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Kennedy's actions to save his surviving crew after the sinking of PT-109 made him a war hero, which proved helpful in his political career.

The incident may have also contributed to Kennedy's long-term back problems. After he became president, the incident became a cultural phenomenon, inspiring a song, books, movies, various television series, collectible objects, scale model replicas, and toys. Interest was revived in May 2002, with the discovery of the wreck by Robert Ballard. PT-109 earned two battle stars during World War II operations.

PT-109 belonged to the PT-103 class, hundreds of which were completed between 1942 and 1945 by Elco in Bayonne, New Jersey. PT-109's keel was laid 4 March 1942 as the seventh Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) of the 80-foot-long (24 m)-class built by Elco and was launched on 20 June. She was delivered to the Navy on 10 July 1942, and fitted out in the New York Naval Shipyard in Brooklyn.

The Elco boats were the largest PT boats operated by the U.S. Navy during World War II. At 80 feet (24 m) and 40 tons, they had strong wooden hulls of two layers of 1-inch (2.5 cm) mahogany planking. Powered by three 12-cylinder 1,500 horsepower (1,100 kW) Packard gasoline engines (one per propeller shaft), their designed top speed was 41 knots (76 km/h; 47 mph).

An official U.S. Navy model, lacking field-mounted 37 mm cannon

The engines were fitted with mufflers on the transom to direct the exhaust under water, which had to be bypassed for anything other than idle speed. These mufflers were used not only to mask their own noise from the enemy, but to improve the crew's chance of hearing enemy aircraft, which were rarely detected overhead before firing their cannons or machine guns or dropping their bombs.

PT-109 could accommodate a crew of three officers and 14 enlisted, with the typical crew size between 12 and 14. Fully loaded, PT-109 displaced 56 tons. The principal offensive weapon was her torpedoes. She was fitted with four 21-inch (53 cm) torpedo tubes containing Mark 8 torpedoes. They weighed 3,150 pounds (1,430 kg) each, with 386-pound (175 kg) warheads and gave the tiny boats a punch at least theoretically effective even against armored ships.

Their typical speed of 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph) was effective against shipping, but because of rapid marine growth buildup on their hulls in the South Pacific and austere maintenance facilities in forward areas, PT boats ended up being slower than the top speed of the Japanese destroyers and cruisers they were assigned to attack in the Solomons. Torpedoes were also useless against shallow-draft barges, which were their most common targets. With their machine guns and 20 mm cannon, the PT boats could not return the large-caliber gunfire carried by destroyers, which had a much longer effective range, though they were effective against aircraft and ground targets.

Because they were fueled with aviation gasoline, a direct hit to a PT boat's engine compartment sometimes resulted in a total loss of boat and crew. In order to have a chance of hitting their target, PT boats had to close to within 2 miles (3.2 km) for a shot, well within the gun range of destroyers. At this distance, a target could easily maneuver to avoid being hit. The boats approached in darkness, fired their torpedoes, which sometimes gave away their positions, and then fled behind smoke screens.

Sometimes retreat was hampered by seaplanes dropping flares to render the boats visible in darkness. They would then attack the boats with bombs and machine gun fire. The firing of the boats' torpedoes imposed an additional risk of detection. The Elco launch tubes used 3-inch (76 mm) black powder charges to expel the torpedoes. Firing of the charge could sometimes ignite the grease with which the torpedoes were coated to facilitate their release from the tubes. The resultant flash could give away the position of the boat. Crews of PT boats relied on their smaller size, speed and maneuverability, and darkness, to survive.

Ahead of the torpedoes on PT-109 were two depth charges, omitted on most PTs, one on each side, about the same diameter as the torpedoes. These were designed to be used against submarines, but were sometimes used by PT commanders to confuse and discourage pursuing destroyers. PT-109 lost one of her two Mark 6 depth charges a month before Kennedy showed up when the starboard torpedo was inadvertently launched during a storm without first deploying the tube into firing position. The launching torpedo sheared away the depth charge mount and some of the footrail.

PT-109 had a single 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft mount at the rear with "109" painted on the mounting base, two open rotating turrets (designed by the same firm that produced the Tucker automobile), each with twin M2 .50 cal (12.7 mm) anti-aircraft machine guns at opposite corners of the open cockpit, and a smoke generator on her transom. These guns were effective against attacking aircraft.

The day before her final mission, PT-109's crew lashed a U.S. Army 37 mm antitank gun to the foredeck, replacing a small, 2-man life raft. Timbers used to secure the weapon to the deck later helped save their lives when used as a float.

PT-109 was transported from the Norfolk Navy Yard to the South Pacific in August 1942 on board the liberty ship SS Joseph Stanton. PT-109 arrived in the Solomon Islands in late 1942 and was assigned to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 2 based on Tulagi island. PT-109 participated in combat operations around Guadalcanal from 7 December 1942 to 2 February 1943 when the Japanese withdrew from the island.

Despite having a bad back, JFK used his father Joseph P. Kennedy's influence to get into the war. He started out in October 1941 as an ensign with a desk job for the Office of Naval Intelligence. Kennedy was reassigned to South Carolina in January 1942 because of his brief affair with Danish journalist Inga Arvad. On 27 July 1942, Kennedy entered the Naval Reserve Officers Training School in Chicago.

After completing this training on 27 September, Kennedy voluntarily entered the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadrons Training Center in Melville, Rhode Island, where he was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) (LTJG). He completed his training there on 2 December. He was then ordered to the training squadron, Motor Torpedo Squadron 4, to take over the command of motor torpedo boat PT-101, a 78-foot Huckins PT boat.

In January 1943, PT-101 and four other boats were ordered to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 14 (RON 14), which was assigned to Panama. He detached from RON 14 in February 1943 while the squadron was in Jacksonville, Florida, preparing for transfer to the Panama Canal Zone.

LTJG John F. Kennedy aboard PT-109, 1943

After the capture of Rendova Island, the PT boat operations were moved to a "bush" berth there on 16 June. From that base, PT boats conducted nightly operations, both to disturb the heavy Japanese barge traffic that was resupplying the Japanese garrisons in New Georgia, and to patrol the Ferguson and Blackett Straits in order to sight and to give warning when the Japanese Tokyo Express warships came into the straits to assault U.S. forces in the New Georgia–Rendova area.

On 1 August, an attack by 18 Japanese bombers struck the base, wrecking PT-117 and sinking PT-164. Two torpedoes were blown off PT-164 and ran erratically around the bay until they ran ashore on the beach without exploding. Despite the loss of two boats and two crewmen, Kennedy's PT-109 and 14 other boats were sent north on a mission through Ferguson Passage to Blackett Strait, after intelligence reports had indicated that five enemy destroyers were scheduled to run that night from Bougainville Island through Blackett Strait to Vila, on the southern tip of Kolombangara Island.

In the PT attack that followed, fifteen boats loaded with 60 torpedoes counted only a few observed explosions. However, of the thirty torpedoes fired by PT boats from the four divisions not a single hit was scored. Many of the torpedoes exploded prematurely or ran at the wrong depth. The boats were ordered to return when their torpedoes were expended, but the boats with radar shot their torpedoes first. When they left, remaining boats, including PT-109, were left without radar, and were not notified that other boats had already engaged the enemy.

Amagiri in 1930

The crew had less than ten seconds to get the engines up to speed, and were run down by the destroyer between Kolombangara and Ghizo Island, near 8°3′S 156°56′E.

Conflicting statements have been made as to whether the destroyer captain had spotted and steered towards the boat. Some reports suggest Amagiri's captain never realized what happened until after the fact. The author Donovan, having interviewed the men on the destroyer, concluded that it was not an accident. Damage to a propeller slowed the Japanese destroyer's trip to her own home base.

The captain of Amagiri was Lieutenant Commander Kohei Hanami. Also aboard was his senior officer, Captain Katsumori Yamashiro (commander, 11th Destroyer Flotilla), and on a following ship was Captain Tameichi Hara (Flotilla commander, Destroyer Div. #7), who claimed he noticed the resulting explosive fire after PT-109 had been rammed, cut in half, and left burning.

PT-109 was cut in two. Seamen Andrew Jackson Kirksey and Harold W. Marney were killed, and two other members of the crew were badly injured. For such a catastrophic collision, explosion, and fire, it was a low loss rate compared to other boats that were hit by shell fire. PT-109 was gravely damaged, with watertight compartments keeping only the forward hull afloat in a sea of flames.

Map of the events of 2 August 1943

The eleven survivors clung to PT-109's bow section as it drifted slowly south. By about 2:00 p.m., it was apparent that the hull was taking on water and would soon sink, so the men decided to abandon it and swim for land. As there were Japanese camps on all the nearby large islands, they chose the tiny deserted Plum Pudding Island, southwest of Kolombangara. They placed their lantern, shoes, and non-swimmers on one of the timbers used as a gun mount and began kicking together to propel it. Kennedy, who had been on the Harvard University swim team, used a life jacket strap clenched between his teeth to tow his badly-burned senior enlisted machinist mate, MM1 Patrick McMahon. It took four hours to reach their destination, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) away, which they reached without interference by sharks or crocodiles.

The island was only 100 yards (91 m) in diameter, with no food or water. The crew had to hide from passing Japanese barges. Kennedy swam to Naru and Olasana islands, a round trip of about 2.5 miles (4.0 km), in search of help and food. He then led his men to Olasana Island, which had coconut trees and drinkable water.

The explosion on 2 August was spotted by an Australian coastwatcher, Sub-lieutenant Arthur Reginald Evans, who manned a secret observation post at the top of the Mount Veve volcano on Kolombangara, where more than 10,000 Japanese troops were garrisoned below on the southeast portion. The Navy and its squadron of PT boats held a memorial service for the crew of PT-109 after reports were made of the large explosion.

However, Evans dispatched islanders Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana in a dugout canoe to look for possible survivors after decoding news that the explosion he had witnessed was probably from the lost PT-109. They could avoid detection by Japanese ships and aircraft and, if spotted, would probably be taken for native fishermen.

Kennedy and his men survived for six days on coconuts before they were found by the scouts. Gasa and Kumana disobeyed an order by stopping by Naru to investigate a Japanese wreck, from which they salvaged fuel and food. They first fled by canoe from Kennedy, who to them was simply a shouting stranger. On the next island, they pointed their Tommy guns at the rest of the crew since the only light-skinned people they expected to find were Japanese and they were not familiar with either the language or the people.

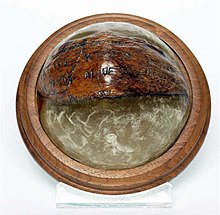

Gasa later said "All white people looked the same to me." Kennedy convinced them they were on the same side. The small canoe was not big enough for passengers. Though the Donovan book and movie depict Kennedy offering a coconut inscribed with a message, according to a National Geographic interview, it was Gasa who suggested it and Kumana who climbed a coconut tree to pick one. Kennedy cut the following message on a coconut:

The coconut with the carved message, cast in a paperweight

Kennedy told Gasa and Kumana, "If Japan man comes, scratch out the message."NAURO ISL

COMMANDER... NATIVE KNOWS POS'IT...

HE CAN PILOT... 11 ALIVE

NEED SMALL BOAT... KENNEDY

The message was delivered at great risk through 35 nmi (65 km; 40 mi) of hostile waters patrolled by the Japanese to the nearest Allied base at Rendova. Other coastwatcher natives who were caught had been tortured and killed. Later, a canoe returned for Kennedy, taking him to the coastwatcher to coordinate the rescue. PT-157, commanded by Lieutenant William Liebenow, was able to pick up the survivors.

The arranged signal was four shots, but since Kennedy only had three bullets in his pistol, Evans gave him a Japanese rifle for the fourth signal shot. The sailors sang "Yes Jesus Loves Me" to pass the time. Gasa and Kumana received little notice or credit in military reports, books, or movies until 2002 when they were interviewed by National Geographic shortly before Gasa's death.

In a more recent visit to the area, writer/photographer Jad Davenport managed to track down the then-90-year-old Eroni Kumana, and together they made a visit to view Kennedy Island. In typical fashion for the time, Kumana reports that the first thing the survivors asked for was cigarettes. When they realized they had no matches, Kumana surprised and delighted the men by making a fire by rubbing two sticks together.

The coconut shell came into the possession of Ernest W. Gibson, Jr. who was serving in the South Pacific with the 43rd Infantry Division. Gibson later returned it to Kennedy. Kennedy preserved it in a glass paperweight on his Oval Office desk during his presidency. It is now on display at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts.

Kennedy's coconut message was not the only message given to the coastwatchers. A more detailed message was written by the executive officer of PT-109, Leonard Jay Thom. Thom's message was a "penciled note" written on paper. Kennedy's message was written on a more hidden location in case the native coastwatchers were stopped and searched by the Japanese.

Thom's message read:

To: Commanding Officer--Oak OThom and Kennedy were both awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. Kennedy was also awarded the Purple Heart for injuries he sustained in the collision. Following their rescue, Thom was assigned as commander of PT-587 and Kennedy was assigned as commander of PT-59 (a.k.a. PTGB-1). Kennedy and Thom remained friends, and when Thom died in a 1946 car accident, Kennedy was one of his pallbearers.

From:Crew P.T. 109 (Oak 14)

Subject: Rescue of 11(eleven) men lost since Sunday, August 1 in enemy action. Native knows our position & will bring P.T. Boat back to small islands of Ferguson Passage off NURU IS. A small boat (outboard or oars) is needed to take men off as some are seriously burned.

Signal at night three dashes (- - -) Password--Roger---Answer---Wilco If attempted at day time--advise air coverage or a PBY could set down. Please work out a suitable plan & act immediately Help is urgent & in sore need. Rely on native boys to any extent

Thom

Ens. U.S.N.R

Exec. 109.

Friday, July 1, 2016

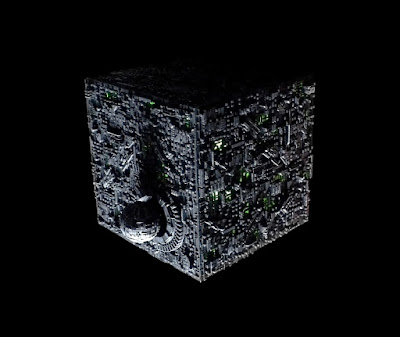

Borg Cube And Sphere From Star Trek "First Contact"

Here are some images of Attack Wing's 8.5" Borg Cube and Sphere from Star Trek "First Contact".

This model started life off as a completed very large game piece painted up in a single steel colour (and not very well either on some panels). But being me I had to make it my own.

When I purchased the model I thought I would have grind little sections to place green gel behind it for lighting. But when I opened the box I discovered to my pleasant surprise that there were holes with green acrylic already behind them, this had already been done at the factory.

To install the lights I had to pop off one of the panels. This was a little tricky without damaging it.

What I did was insert an Exacto knife into one of the edges at one of the corners. I then lightly tapped the Exacto knife down one edge with a hammer while the seal gradually gave way. I then did it on the remaining three sides and off she came.

The interior is made up of an inner transparent acrylic green box with the model panels glued to the outside.

For lighting I wrapped a pole of proper length with LED strip lighting, then placed it in the middle of the model with the wiring running through a hole on the bottom.

I then checked for light leaks. I discovered that the interior around the Borg Sphere launch bay had to be painted black as light was coming through.

Before placing the panel back I had to make an inner ribbon around the interior edges to prevent light leakage along the seams.

I then covered the model in a black wash followed by German grey accenting and a flat coat. I found the flat coat necessary as it reduced the sheen of the steel paint and gave it an overall blended look.

From Wikipedia"

The Borg first appear in the Star Trek: The Next Generation second-season episode "Q Who?", when the omnipotent life-form Q transports the Enterprise-D across the galaxy to challenge Jean-Luc Picard's assertion that his crew is ready to face the unexplored galaxy's unknown dangers and mysteries. The Enterprise crew is quickly overwhelmed by the relentless Borg, and Picard eventually asks for and receives Q's help in returning the ship to its previous coordinates in the Alpha Quadrant. At the episode's conclusion, Picard suggests to Guinan that Q did "the right thing for the wrong reason" by showing the dangers they will eventually face. It is suggested that the Borg may have been responsible for the destruction of Federation and Romulan colonies in the final episode of season one, "The Neutral Zone".

The Borg next appear in The Next Generation's third-season finale and fourth-season premiere, "The Best of Both Worlds". In the third-season cliffhanger, Picard is abducted and subsequently assimilated by the Borg and transformed into Locutus, the Latin term for "he who has spoken" or "he who speaks". "Locutus" is the Borg method of describing the former Picard as the representative of the Borg in all future contacts related to humanity. Picard's knowledge of Starfleet is gained by the collective, and the single cube easily wipes out all resistance in its path, notably the entire Starfleet armada at Wolf 359, which consisted of 40 starships, some of which were sent from the Klingon Empire. The Enterprise crew manages to capture Locutus and gain information through him which allows them to destroy the cube. Picard is later "deassimilated", a process quite different from what happened to Seven of Nine in Star Trek: Voyager (Seven of Nine had to be totally "Re-schooled" on humanity, Picard merely needed to be reminded of humanity).

In the fifth-season episode "I, Borg", the Enterprise crew rescues a solitary adolescent Borg who is given the name "Hugh" by Chief Engineer Geordi La Forge. The crew faces the moral decision of whether or not to use Hugh (who begins to develop a sense of independence as a result of a severed link to the collective consciousness of the Borg) as an apocalyptic means of delivering a devastating computer virus that would theoretically destroy the Borg, or to humanely allow him to return to the Borg with his individuality intact. They decide to return him without the virus. This is followed up in the sixth-season cliffhanger "Descent", which depicts a group of rogue Borg who had "assimilated" individuality through Hugh. These rogue Borg fell under the control of the psychopathic android Lore, the "older brother" of Data.

In cult leader-like fashion, Lore had manipulated them into following him by appealing to their restored emotions and exploiting their new-found senses of individuality and fear, hoping to turn them on the Federation. Lore also corrupts Data through the use of the emotion chip he had stolen from Noonien Soong (Data and Lore's creator). In the end, Data's ethical subroutines are restored (having been suppressed by Lore through use of the emotion chip) and he manages to deactivate Lore after a battle in which a renegade Borg faction led by Hugh attacks the main complex. Data reclaims the emotion chip, Lore is mentioned as needing to be dismantled (for safety) and the surviving Borg fall under the leadership of Hugh. The fate of these deassimilated Borg is not revealed, though non-canon material suggests that they remained on the planet and established a permanent colony.

The Borg return as the antagonists in one of the Next Generation films, Star Trek: First Contact. After again failing to assimilate Earth by a direct assault in the year 2373, the Borg travel back in time to the year 2063 to try to stop Zefram Cochrane's first contact with the Vulcans, which would have erased the Federation from history. However, the Enterprise-E follows the Borg back in time and the crew restores the original timeline. First Contact introduces the Borg Queen, a recurring character on Star Trek: Voyager.

Parts of this destroyed Borg sphere, along with at least two drones, are shown to have crash landed in the Arctic in the Star Trek: Enterprise episode "Regeneration".

This model started life off as a completed very large game piece painted up in a single steel colour (and not very well either on some panels). But being me I had to make it my own.

When I purchased the model I thought I would have grind little sections to place green gel behind it for lighting. But when I opened the box I discovered to my pleasant surprise that there were holes with green acrylic already behind them, this had already been done at the factory.

To install the lights I had to pop off one of the panels. This was a little tricky without damaging it.

What I did was insert an Exacto knife into one of the edges at one of the corners. I then lightly tapped the Exacto knife down one edge with a hammer while the seal gradually gave way. I then did it on the remaining three sides and off she came.

The interior is made up of an inner transparent acrylic green box with the model panels glued to the outside.

For lighting I wrapped a pole of proper length with LED strip lighting, then placed it in the middle of the model with the wiring running through a hole on the bottom.

I then checked for light leaks. I discovered that the interior around the Borg Sphere launch bay had to be painted black as light was coming through.

Before placing the panel back I had to make an inner ribbon around the interior edges to prevent light leakage along the seams.

I then covered the model in a black wash followed by German grey accenting and a flat coat. I found the flat coat necessary as it reduced the sheen of the steel paint and gave it an overall blended look.

From Wikipedia"

The Borg first appear in the Star Trek: The Next Generation second-season episode "Q Who?", when the omnipotent life-form Q transports the Enterprise-D across the galaxy to challenge Jean-Luc Picard's assertion that his crew is ready to face the unexplored galaxy's unknown dangers and mysteries. The Enterprise crew is quickly overwhelmed by the relentless Borg, and Picard eventually asks for and receives Q's help in returning the ship to its previous coordinates in the Alpha Quadrant. At the episode's conclusion, Picard suggests to Guinan that Q did "the right thing for the wrong reason" by showing the dangers they will eventually face. It is suggested that the Borg may have been responsible for the destruction of Federation and Romulan colonies in the final episode of season one, "The Neutral Zone".

The Borg next appear in The Next Generation's third-season finale and fourth-season premiere, "The Best of Both Worlds". In the third-season cliffhanger, Picard is abducted and subsequently assimilated by the Borg and transformed into Locutus, the Latin term for "he who has spoken" or "he who speaks". "Locutus" is the Borg method of describing the former Picard as the representative of the Borg in all future contacts related to humanity. Picard's knowledge of Starfleet is gained by the collective, and the single cube easily wipes out all resistance in its path, notably the entire Starfleet armada at Wolf 359, which consisted of 40 starships, some of which were sent from the Klingon Empire. The Enterprise crew manages to capture Locutus and gain information through him which allows them to destroy the cube. Picard is later "deassimilated", a process quite different from what happened to Seven of Nine in Star Trek: Voyager (Seven of Nine had to be totally "Re-schooled" on humanity, Picard merely needed to be reminded of humanity).

In the fifth-season episode "I, Borg", the Enterprise crew rescues a solitary adolescent Borg who is given the name "Hugh" by Chief Engineer Geordi La Forge. The crew faces the moral decision of whether or not to use Hugh (who begins to develop a sense of independence as a result of a severed link to the collective consciousness of the Borg) as an apocalyptic means of delivering a devastating computer virus that would theoretically destroy the Borg, or to humanely allow him to return to the Borg with his individuality intact. They decide to return him without the virus. This is followed up in the sixth-season cliffhanger "Descent", which depicts a group of rogue Borg who had "assimilated" individuality through Hugh. These rogue Borg fell under the control of the psychopathic android Lore, the "older brother" of Data.

In cult leader-like fashion, Lore had manipulated them into following him by appealing to their restored emotions and exploiting their new-found senses of individuality and fear, hoping to turn them on the Federation. Lore also corrupts Data through the use of the emotion chip he had stolen from Noonien Soong (Data and Lore's creator). In the end, Data's ethical subroutines are restored (having been suppressed by Lore through use of the emotion chip) and he manages to deactivate Lore after a battle in which a renegade Borg faction led by Hugh attacks the main complex. Data reclaims the emotion chip, Lore is mentioned as needing to be dismantled (for safety) and the surviving Borg fall under the leadership of Hugh. The fate of these deassimilated Borg is not revealed, though non-canon material suggests that they remained on the planet and established a permanent colony.

The Borg return as the antagonists in one of the Next Generation films, Star Trek: First Contact. After again failing to assimilate Earth by a direct assault in the year 2373, the Borg travel back in time to the year 2063 to try to stop Zefram Cochrane's first contact with the Vulcans, which would have erased the Federation from history. However, the Enterprise-E follows the Borg back in time and the crew restores the original timeline. First Contact introduces the Borg Queen, a recurring character on Star Trek: Voyager.

Parts of this destroyed Borg sphere, along with at least two drones, are shown to have crash landed in the Arctic in the Star Trek: Enterprise episode "Regeneration".

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)