From Wikipedia"

CSS David was a Civil War-era torpedo boat. On October 5, 1863, she undertook a partially successful attack on the USS New Ironsides, then participating in the blockade of Charleston, South Carolina.

Based upon a design by St. Julien Ravenel, the David was built as a private venture by T. Stoney at Charleston, South Carolina, in 1863, and was put under the control of the Confederate States Navy. Eventually over twenty torpedo boats of the David type were built for and operated by the CSN. The cigar-shaped boat carried a 32 by 10 inch (81 × 25 cm) explosive charge of 134 pounds (about 60 kilograms) gunpowder on the end of a spar projecting forward from her bow. CSS David operated as a semi-submersible: water was taken into ballast tanks so that only the length of the open-top conning tower and the stack for the boiler appeared above water. Designed to operate very low in the water, David resembled in general a submersible submarine; she was, however, strictly a surface vessel. Operating on dark nights, and using anthracite coal (which burns without smoke), David was nearly as hard to see as a true submarine.

On the night of October 5, 1863, David, commanded by Lieutenant William T. Glassell, CSN, left Charleston Harbor to attack the casemated ironclad steamer USS New Ironsides. The torpedo boat approached undetected until she was within 50 yards of the blockader. Hailed by the watch on board New Ironsides, Glassell replied with a blast from a shotgun and David plunged ahead to strike. Her spar torpedo detonated under the starboard quarter of the ironclad, throwing high a column of water which rained back upon the Confederate vessel and put out her boiler fires. Her engine dead, David hung under the quarter of New Ironsides while small arms fire from the Federal ship spattered the water around the torpedo boat.

Believing that their vessel was sinking, Glassell and two others abandoned her; the pilot, Walker Cannon, who could not swim, remained on board. A short time later, Assistant Engineer J. H. Tomb swam back to the craft and climbed on board. Rekindling the fires, Tomb succeeded in getting David's engine working again, and with Cannon at the wheel, the torpedo boat steamed up the channel to safety. Glassell and Seaman James Sullivan, David's fireman, were captured. New Ironsides, though not sunk, was damaged by the explosion. US Navy casualties were Acting Ensign C.W.Howard (died of gunshot wound), Seaman William L. Knox (legs broken) and Master at Arms Thomas Little (contusions).

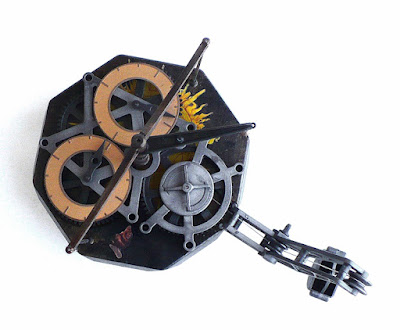

Photograph of a captured David-class torpedo boat (possibly CSS David herself), taken after the fall of Charleston in 1865

The wreck of the CSS David

David's last confirmed action came on April 18, 1864 when she tried to sink the screw frigate USS Wabash. Alert lookouts on board the blockader sighted David in time to permit the frigate to slip her chain, avoid the attack, and open fire on the torpedo boat. Neither side suffered any damage.

The ultimate fate of David is uncertain. Several torpedo boats of this type fell into Union hands when Charleston was captured in February 1865. David may well have been among them.

January 20, 1998, underwater archaeologist Dr. E. Lee Spence led a Sea Research Society expedition, funded by philanthropist Stanley M. Fulton, to find the remains of the two Confederate torpedo boats shown in various photos taken shortly after the fall of Charleston. Spence's theory was that the two vessels had been abandoned where they lay and were simply filled over as the city expanded. Spence used still existing houses in the pictures to triangulate where they might be. Using a ground penetrating radar, operated by Claude E. "Pete" Petrone of National Geographic Magazine, the expedition located two radar anomalies consistent with what would be expected of the two wrecks. The anomalies were under present-day Tradd Street, so no excavation was done. A post-war letter written by David C. Ebaugh, who supervised the construction of the David, described it as abandoned at what was then the foot of Tradd Street.